![3530415915_98802751ea[1] 3530415915_98802751ea[1]](https://marthamcphee.files.wordpress.com/2009/10/3530415915_98802751ea1.jpg?w=1100)

A beautiful little sister and a homely older one — Kathryn, Thelma. 1910. An intrepid mother who wants freedom from a husband and the confining life of a wife. They run away to Montana — beneficiaries of the homestead act of 1909 — leaving Vernon behind in Ohio to find a letter saying they are gone. The girls are afraid, wonder what will become of them. It’s winter and cold and they ride in the 3rd class car of the train, a coal fire in the center, around which passengers hover, trying to stay warm. The mother, Glenna, though she doesn’t have money (only what she’s been able to steal from Vernon’s pockets), has a sense of class and finery. She carries with her a harp (yes a big, beautiful harp that she can play like an angel). She carries a trunk of summer dresses and an iron and ribbons for her daughters’ hair and they look impeccable, if cold, in white linen. She carries too her own great grandmother’s China wedding bowl and Temple Notes to Shakespeare. She’s a reader, a dreamer, ambitious and will not be trapped. In Montana there are jobs for women and she wants to work, wants to earn money, wants to feel the power of providing for herself and her girls. She loves men and loves to flirt and when the train gets stuck in a snow drift it is not long before she’s playing her harp for the gentlemen in first class, warm in a Pullman Sleeping Car with fine Scotch.

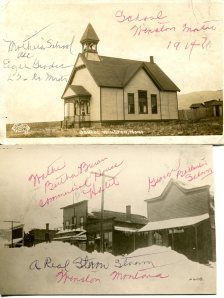

Glenna’s school house in Winston, Montana. And the town covered in snow.

My grandmother, my great grandmother — snippets of story. The frontier at a moment that welcomed women, offering opportunity. (Montana would elect the first woman to the House of Representatives in 1914.) Who were these women? Of course, I knew my grandmother well. I adored her, adored listening to her elaborate stories of our lineage. I could imagine her as a little girl, learning the tales of where we came from, from the refined Glenna who refused to accept that her circumstances were what they were, that she wasn’t a queen or a duchess. But it didn’t matter now because she had been and would be again. Her life didn’t begin when she was born; it would not end when she died. Rather, she was just one link in a miraculous continuum, that reached back to Germany and Scotland, that included men like Helmut von Keller, advisor to Bismark from Mechlenburg-Schwerin along the Baltic Sea and women like Mary Queen of Scots and the Royal Stewarts of Nairn — princes and duchesses and queens and the War of 1812 that brought some of her people to America where their children and children’s children became novelists (James Fenimore Cooper among them) and the first woman to go to college and fine painters of the human anatomy who stole cadavers from graves. One started the Dole pineapple empire and another became the milliner for Granny Taft, William Howard Taft’s aunt. They survived the Civil War. They were fabulously wealthy and then lost it all in the various 19th century runs on banks. From my grandmother’s telling, the lineage made perfect sense — her mother’s line (German), her father’s line (Scottish). They were nobles both, cast on the shores of America by war and the great hope of something more. Her details were precise, born it seemed to me, of a fierce imagination. James von Slagle, her great great grandfather, came to America during the War of 1812 as a military advisor to Major General Andrew Jackson and saw to the training of rough, unschooled farmers, preparing them for battle against the Indians. He led his troop in the battle of Horseshoe Bend on the shores of the Tallapoosa River in Alabama in 1814, a success that would make him a national hero. In a picture of James von Slagle that my grandmother described, he had the finest mustache and the broad strength of an aristocrat, “Von,” she told me, “indicates noble birth.”

The stories were Glenna’s who died long before I was born, but who has lived in my imagination ever since I was a girl through the stories retold to me by my grandmother. And now, finished with a fourth novel, there are days such as this, in which I begin to dream about writing a fifth novel. 1910 — the 20th century spreading out before Thelma and Kathryn and Glenna — the long road their lives will follow.

She wondered what would become of them — the novel could begin as the three head west on the train in winter, pioneers. Who would these women be (alive in the continuum of their descendents) at the end of the 20th century, a century in which so much changed for women? Here is where fiction starts for me: at the intersection of memory and imagination.

Glenna and Thelma posing on wooden horses during a long stopover in Saint Louis, on their way home to Ohio in 1914 for Christmas

Kathryn, the beautiful younger sister.

those images were hilarious. A+

Why thank you. I’m glad you enjoyed them.