Jenny, my sister, is now reviewing for Bookslut, the brilliant book review site. She has a column called The Bombshell. Read it and enjoy. Also be aware: she’s about to launch her own site any day now: jennymcphee.com.

Category: FAMILY

Fog: They Vanished Then Returned

Crazy Chicks

Do You Want To Be Inspired? Read This:

The other night my younger sister, Joan Sullivan, was honored by the Bronx Academy of Letters for being its founding principal. She is now Deputy Mayor of Education for the City of Los Angeles. This is the speech she delivered:

I want to get one thing straight. This school was not founded by me.

The school, itself a political act, was founded by a long series of political movements that erupted in the 1960s. It was founded by The Young Lords, who took over hospitals and churches to demand that they operate programs for the poor and who led campaigns to force the City of New York to increase garbage pick-up in neighborhoods like ours, ones that suffered from chronic institutional neglect.

This school was founded by Piri Thomas, a Puerto Rica-Cuban born poet and freedom fighter, who was raised in the barrios of New York and whose name is emblazoned on our school’s walls.

I’m on stage, honored of course by this award, but this school does not belong to me.

The Bronx Academy of Letters is based on the word and sits in the community that gave birth to Hip Hop. The school belongs to KRS-1, a man who continues to use music to fight for social change. This school belongs to the Bronx.

I can’t take credit for this school. This school belongs to its stakeholders.

– It belongs to Richard Kahan, the Urban Assembly, and our Board, who understand that school reform is about building partnerships and who understand that the era of public schools being the exclusive domain of government is over.

– It belongs to immigrants from the Dominican Republic, China and Ghana who saw school as the avenue to success and brought us their brilliant children.

– It belongs to students who, out of boredom and frustration, spent decades protesting poorly run and resourced classrooms.

– It belongs to Qian, Stacey, Jeffrey, and Lucelys who graduated first from the Bronx Academy of Letters and who are now preparing to graduate from Skidmore, Wesleyan, Ithaca, and Columbia.

– It belongs to our teachers, who are scientists, writers, dancers, athletes, and scholars and who have put every drop of their art and genius into their teaching.

This school belongs to all of you, our supporters, who saw that the young people living across the Madison Avenue Bridge in the South Bronx were not only part of your community, but also a part of your future.

If this school belongs to me at all, it belongs to my mother who with her indomitable will, bribed me to read books as a child until I found Roald Dahl and became a willing reader and a capable writer. And to my father, who believed in fairytales and who, when I was five and asked to go on a picnic in a blizzard, took me down to the banks of the Delaware River and set up a picnic in the snow. And to my 9 sisters and brothers, who played so beautifully with ideas and whose books and politics imbued me with a determination to fight and the courage to hope. And to my wife, Ama, who has revealed with her intellect and spirit such a joyful world to me.

All of this is to say that the idea of a founder is a farce. We have all founded this school that continues to be found every day by students, teachers, parents and you. This school belongs to you—which is a gift, a promise, a responsibility.

Because anything that is found can be lost, lost to financial and budget crises, lost to layoffs that disproportionately affect our poorest neighborhoods, lost to those who forget that the Bronx Academy of Letters and its children areour legacy.

And there are more things yet to be found. We need more than a good school. We need lots of good schools. We need them here and in Los Angeles. We need affordable college access and to begin talking not about K through 12 but about Pre K through college. Just as we, together, found each other and this school. We can find strong school systems and turn these into strong communities, knowing that we will never have strong communities without strong schools.

This sounds impractical, untenable. So was the Bronx Academy of Letters. So was the idea of opening a school in America’s poorest congressional district with an open admissions policy and with the goal of sending its graduates to our nation’s best colleges. So is my request of you tonight. I ask that you take joy in and responsibility for founding this school. I ask that you continue finding this school and that you remember that its students will find the things we lost and the things we never even believed to be possible.

____________________________

There is one other thing. You should know that this school also belongs to our new leader. A woman I interviewed right here in the Italian Academy before hiring her as our school’s first teacher. A woman who started building and leading with humility, integrity, and passion before our doors even opened. A woman who proposed and then assembled our middle school. An inspired English teacher, a devoted advisor, an award-winning poet, a friend and mentor. Please join me in welcoming the person who has now worked for this school longer than any other, Principal Anna Hall.

CLICK HERE TO DONATE

Happy Mother’s Day

Please Come With Me To The BAL

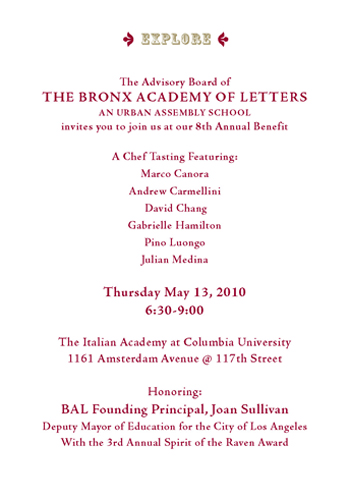

On Thursday, May 13 at 6:30 PM the Advisory Board of the Bronx Academy of Letters will be honoring my youngest sister, Joan Sullivan, at the school’s 8th Annual Benefit. Joan is the Founding Principal of the BAL, a former All-American lacrosse player at Yale University. She was recently appointed the Deputy Mayor of Education for the City of Los Angeles. She is also a brilliant and inspired speaker.

She began the BAL, a New York City public middle and high school, 8 years ago with the simple idea that she wanted to give to her students some of the best things she had had as a student: quality education; chances to travel; a strong library; a vibrant music and drama program; serious athletics; and most of all a path to college. And she wanted to bring all this to under-served students in the South Bronx. When she left the school for her position in Los Angeles she left behind a thriving well-structured school. But it continues to need all of our support so that all the extras that make for a complete and rich education can be afforded these students.

The event will be held at the Italian Academy at Columbia University, and will include a chef tasting featuring some of the city’s finest chefs: Marco Canora (formerly with Craft), Andrew Carmellini (most recently with A Voce), David Chang (Momofuku), Gabrielle Hamilton (Prune), Pino Luongo (Centolire) and Julian Medina (Yerba Buena).

I promise it will be a great time while also supporting a great cause! If you would like to purchase a ticket ($150) for the event on May 13, please click on the link below.

To purchase tickets please click here

Proofread Your Heart

Oh no, my daughter is a poet.

Proofread Your Heart

When hatred takes over

your heart, whisper to me

when your goddess fails

whisper

when the world is gone

whisper

because

there

is

an answer

when the sound of

guns and bullets

crashes down

whisper to me for even

up here

I can hear.

— Livia Svenvold McPhee, 10 years old

My Husband is a Poet: It’s Poetry Month

A Crossing

From them the dust and from them the storm,

and the smoke in the sky, and a rumble in the ground;

and from them the very sky seeming, from afar, parabolic;

from the curve or girth beyond the eye’s reach;

from/across/& through—

a beautiful level and fertile plain—

with soggy bottoms of slender allium

or nodding onion the size of musket ball,

white, crisp, well-flavored; from the high grass stretching

into tomorrow

the welcoming committee assembles & gathers—

each dark visage a massive escarpment

that stares out of bewilderment;

—from their river crossing, and from somewhere

inside the huff, hieratic ohm—

the beck-and-echo, returning call

of calves mothering-up; from the dark script

of the herd, frequently approaching more nearly

to discover what we are,

with/across/& to

the cataract of time:

this steady, animal regard,

this gaze of theirs, the size and scale of it,

so amassed,

arrests the men, who look them back

as they must/& do/& will—

from a bookcase, from a window sill.

From Empire Burlesque by Mark Svenvold

My Valentine

Jasper’s due date was my daughter’s birthday. She was turning four that year and I worried that she’d feel neglected if Jasper arrived on her day. A friend suggested I throw Livia a big party a few weeks before. I chose Valentine’s Day. I invited all her friends and all their parents and made an enormous feast and decorated the apartment and ordered a ridiculously expensive cake. Jasper’s arrival would not steal from her. The night before the party, having just finished the last preparations, I lay down. My mother, who was coming to help, called to say she was stuck in traffic at the Lincoln Tunnel. I told her not to worry, that I was in good shape for the party. Just then I felt an enormous gush of water. “I think my water just broke,” I said to my mother. Indeed it had. Jasper was born the next day, Valentine’s Day. And, of course, Livia didn’t care. And now 6 years later this is Jasper’s favorite story. He asks me to repeat it all the time. We have told him he couldn’t wait, he wanted to be at the party, that he likes to be right in the middle of everything—where the action is. “I love to be in the middle of everything,” he says. My love, my Valentine for life.

Travel Is the Most Important Form Of Education

We went to Haiti when I was twelve years old. My stepfather, Dan, believed his kids should know the world, that traveling was the most important form education. If it had been up to him we wouldn’t have gone to school. Rather we would have traversed the globe. We went to Haiti because he loved it. He had been both divorced and then remarried (to my mother) there. Their honeymoon was a hike from Kenscoff to Marigot through the mountains. It was unclear if the divorce and the marriage were recognized in the States, but they were recognized by Dan and in turn by us, his ten children, so the rest didn’t really matter.

My mother and Dan on their honeymoon

We went for the month of August and stayed in Port-au-Prince at the Oloffson Hotel. The older kids read The Comedians, all of us learned about Graham Greene.

After a few days, we went to Jacmel, piling into a painted truck with wobbly wheels. It carried us over a mountain pass on a road that the French were constructing but that wasn’t quite finished. We were warned it was too dangerous and that we shouldn’t attempt it. Dan disagreed. Huge ruts, potholes the size of ponds, hairpin turns, sheer drops, no guard rails — no matter. Somehow we’d manage. Dan believed in the impossible always being possible. In the middle of the night we had to give up and retreat, back to Port-au-Prince. The next day we boarded a tiny plane and flew to Jacmel, landing on a grass runway. We stayed in a French colonial house with filigree balconies overlooking the sea. It was owned by Selden Rodman, an art dealer famous for bringing Haitian art to the white world. The ground floor of the house was an art gallery.

Many of us on the Jacmel Veranda

Haitian art was everywhere. And Dan seemed to buy up a good amount of it with money he didn’t have, borrowed from friends and his wealthy first wife: colorful paintings, steel drums flattened and carved into trees and birds and flowers, wood panels describing the Madonna breast-feeding baby Jesus, a pair of lovers. Dan’s idea, you see, was to open a Haitian art gallery himself, in New Hope, Pennsylvania not far from our home.

I remember a dinner in Port-au-Prince with local artists high up in hills above the city in a beautiful home. Names cast about: Gorgue and Gerard Paul and Andre Pierre and Jerome Polycarpe and Audes Saul and Hyppolite and S.E. Bottex — some living, some dead: all possessing a mystery in their art that Rodman described as the crystallization of joy. I remember the crates holding the art that we transported home.

I remember visiting art markets, all of us allowed to choose our own painting.

Sarah chose an extra one, of Eve plucking the apple from the tree while Adam watched. She paid for it herself. The artist was famous, named Cherisme. Even at 16 she had an impeccable eye.

Sarah with her Cherisme in Jacmel

The art was stored in our home, is to this day — hanging on all the walls. The wood carvings, the paintings of Virgin Marys and funeral processions and bright peach-colored flamingos and fish and turkeys, an enormous blue crab, and women carrying baskets of fruit, water in buckets on their heads, of a whole village of people praying outside a church, of festivals, of voodoo ceremonies presided over by voodoo priests, jungle scenes. A screen with blue owls, the repetition making the familiar bird a comforting abstraction. The gallery is now long gone, my stepfather dead. My mother, strapped for cash a few years ago, was told to sell her collection of Haitian art. She refused. “I love it,” she said. “I will not ever let it go.”

But I digress. It was an education Dan, and my mother, wanted to give to us. They wanted us to understand what the world was, that it was much more complicated than the small and safe circumference of our comfortable (if exotic hippie) life in Ringoes, New Jersey. On the streets of Haiti I began to see a world that I had not known before, a world that began to open up my twelve-year-old eyes. I saw people who had walked for miles to sell their food at the market. I saw people disfigured by disease. I saw small children with distended bellies. I saw an old woman die in the road. I saw soldiers with AK47s and learned of the TonTon Macoutes and of Papa Doc and Baby Doc Duvalier. I began to understand that governments weren’t all the same and that people worked hard and starved anyway. I was told that because the French were defeated by the Haitians so long before, the United States directly benefited, bought a large chunk of the south (the Louisiana Purchase) for next to nothing, pennies per acre, from the French for whom it no longer served. In short, I began to understand that nothing swims isolated and alone in the universe. I landed in the middle of a crazy, beautiful jungle — a world that felt so very far removed from my own, totally unique. But by pulling on a string one could also find a through-line linking Africa and Louisiana and somehow even me.

Dan and my mother wanted us to understand something that is a rare commodity these days — they wanted us to appreciate complexity. They wanted us to know that we are not all the same — know that there is nuance and struggle and tremendous beauty (the falls at Bassins Bleus that you can only get to on horseback — along a palm fringed beach, up jagged switch -backs in a mountain pass), that the world thinks many different things, people live many different ways — some because they can, others because they must. And it was their belief that if we understood this, that our minds would begin to seek complexity and even begin to suspect or distrust simple, reductive views of the world, as compelling as simplicity can be. Travel taught me that our culture, with all it has to offer, all its power and possibility and privilege, is but one small and limited portal on the truth of life’s vast and horrifying and marvelous spectrum.