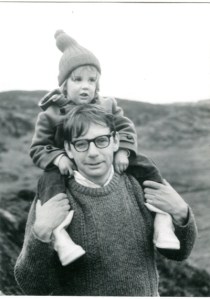

I’ve been traveling since I was a toddler. My mother and father and sisters and I took an ocean liner from New York City to England because my parents were afraid to fly. Young as I was I still remember little things. I remember that two of my sisters got sea sick out in the middle of the Atlantic, the great boat bobbing about and my sisters throwing up into bags tied to the bed posts. My sisters were green. On the deck we wrapped in blankets and listened to the ocean. It was April and cold. In London we had tea at Brown’s, tiny, crustless sandwiches presented on a tiered, silver tray. And after I recall believing that my mother was going to drive the taxi because she got in that side of the car. Somewhere we picked up the red VW bus and drove it to Spain, then to France, then to Scotland, to the Island of Colonsay where the McPhees come from, farmers originally — the island’s poorer folk. We lived there for six months while my father did research and wrote The Crofter and the Laird and my sisters went to a one-room school house and made little Scottish friends. I remember sitting on my father’s shoulders and tapping him with my heels as if he were a horse and saying, “Run, Daddy, run.” And he would run, at the edge of the sea, across the moors, thrilled by my delight and adventure and curiosity, and I’d kick him just a little bit more if he dared to slow down. “Run, Daddy, run.” I was traveling. I remember nothing more of the trip, but have been traveling ever since.

Out of the blue, as I was writing the above, my father emailed me the following — brief notations, a scribbled itinerary:

1967, April through September. Six months in Europe with entire

family, researching “The Crofter and the Laird”, “Pieces of the Frame”,

“Josie’s Well”, “From Birnam Wood to Dunsinane”, “Twynam of Wimbledon”, and

“Templex” (these pieces were written over the next couple of years). To

Bath, April 25. To Colonsay, May 1. May 6, climb Kilchattan hills (“Run,

Daddy, run.”) May 11, Balaromin Mor. May 23, Donald Garvard. May 24,

Oronsay — Andrew Oronsay. May 25, the Ardskenish Peninsula. June 4, Martha

baptized in the Church of Scotland. June 6, leave island. June 12, Loch

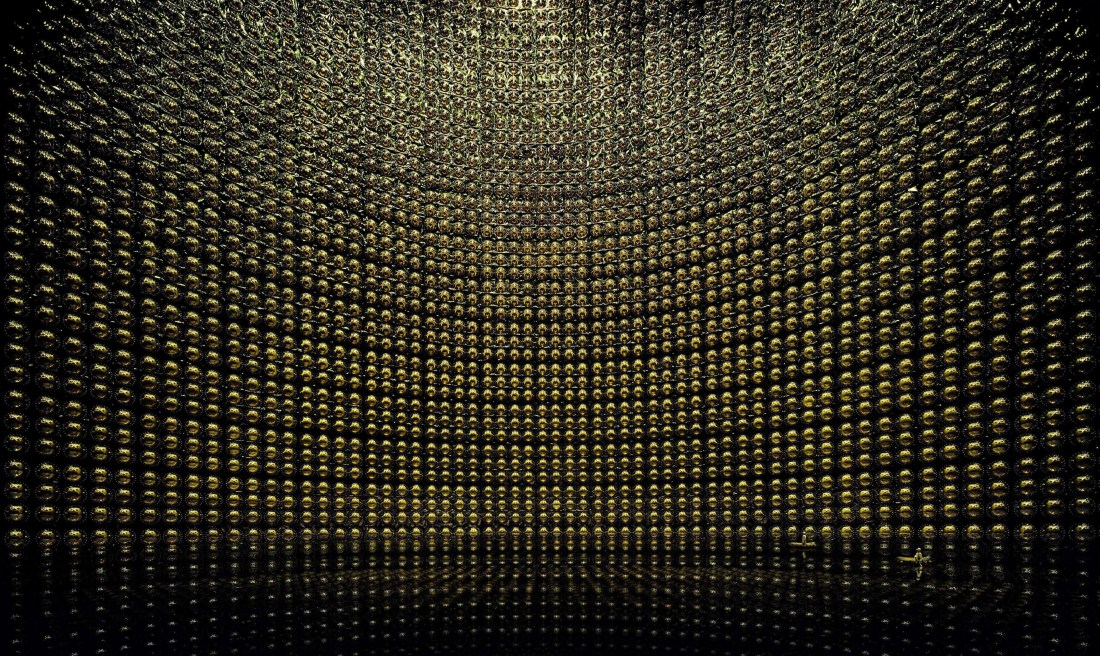

Ness Phenomenon Investigation Bureau. June 13, Dame Flora McLeod of McLeod,

Station Hotel, Inverness. June 14, Captain Smith Grant, Glenlivet. Then

George C. Harbinson, Macallan, Cragellachie. June 15, Donald and Jean

Sinclair, Dunsinnan. Later Sir Ian Moncreiff of that Ilk, Easter Moncreiff.

June 19-26, London, Wimbledon, Robert Twynam. June 27, France. July 4, by

ship from Valencia to Mallorca. July 25, leave Mallorca. August 1-4,

Madrid. August 5, La Granja, Segovia, camped Avila. August 6, camped

Salamanca. August 9 to September 7, Suances. August 20, arrive New York.

My three-year-old’s memory was a little off – – Colonsay first, etc. So much for memory generally. Memory is fiction. My father, 36 at the time, makes a mistake even with the final dates. Details aside, of their daughters our parents made travelers.